Cybersecurity regulations have been multiplying since the 2010s, and this trend continues, driven by the intensification of threats, the rapid rise of new technologies, the growing dependence of businesses on IT, and an unstable geopolitical context. While this trend aims to better protect economic actors and critical infrastructures, it also creates increasing complexity for companies, particularly those with a significant international footprint, which must navigate a patchwork of often heterogeneous regulations. In this context, more than 76% of CISOs believe that the fragmentation of regulations across jurisdictions significantly affects their organizations’ ability to maintain compliance[1].

In this article, we review the latest cybersecurity regulatory updates and the challenges they pose, and we propose two approaches to best manage the accumulation of regulations.

Current landscape: A continuing proliferation of cybersecurity regulations

In Europe, a strengthening of cybersecurity laws and an expansion of scope

In recent years, the European Union has continued its regulatory momentum in cybersecurity and resilience, following the implementation of structuring regulations such as DORA, NIS2, CRA, and the AI Act. These regulations also concern a larger number of actors, particularly with an extension of the regulated sectors.

The first is the DORA regulation. Entered into force in January 2025, it imposes obligations on financial entities to strengthen their digital resilience, focusing on four main areas: ICT risk management, incident management, operational resilience testing, and ICT service provider risk management.

The NIS2 directive, which came into force in October 2024, expands the objectives and scope of NIS1. It now applies to two types of entities:

- Essential Entities (EE) – previously known as Operators of Essential Services (OES) in NIS1. However, the list of applicable sectors has significantly expanded.

- Important Entities (IE) – this new category aims to support the development of digital uses in society. It includes, for example, the manufacturing sector of IT equipment. IEs are considered less critical than EEs, so the obligations imposed on them at the national level will be less stringent.

Meanwhile, the EU also adopted the Directive on the Resilience of Critical Entities (REC), also effective from October 2024. It requires critical infrastructure operators to implement measures to prevent, protect against, and manage risks, ensuring continuity of vital services essential to the Union’s economic and social stability.

The NIS2 and REC directives had to be transposed into national laws by 17 October 2024. As of now, only a few Member States have completed this process. In France, following a first vote in the Senate on 12 March 2025, the bill is now before the National Assembly, with a public session scheduled for mid-September.

To further address cybersecurity risks linked to digital products, the EU adopted the Cyber Resilience Act, effective since 10 December 2024. This regulation applies to both standard digital products (e.g. consumer devices, smart cities) and critical digital products (e.g. firewalls, industrial control systems). It requires these to be free of known vulnerabilities, properly documented, and subject to structured vulnerability management.

Outside the EU, the United Kingdom has also strengthened its regulatory framework. Faced with rising cyberattacks on critical sectors like the NHS and Ministry of Defence and recognizing a lag in legislative adaptation, the UK government presented the Cyber Security and Resilience Bill in April 2025. The bill draws inspiration from NIS2 and aims to boost national resilience against growing cyber threats.

A similar dynamic in Asia

Cybersecurity regulations have also been strengthened in Asia in recent years, particularly in China and Hong Kong.

In China, the Network Data Security Management Regulations came into effect on January 1st, 2025. It complements, clarifies, and extends the obligations arising from previous regulations (CSL, DSL, PIPL). It covers all electronic data processed via networks, including non-personal data, and is structured around three main axes:

- The protection of personal data, with a focus on explicit consent, transferability, and transparency;

- The management of important data, requiring their identification, documentation, and security;

- The accountability of large digital platforms, subject to enhanced obligations in terms of governance, transparency, and algorithmic ethics.

In Hong Kong, a new measure aimed at strengthening the security of critical infrastructure was adopted on March 19th, 2025, and is set to come into effect on January 1st, 2026. The main requirements of the Computer Systems Bill are centered around four themes: an enhanced organizational structure (local presence, cybersecurity unit, change reporting), threat prevention (security plan, annual assessment, audit), incident management (rapid notification, response plan, written report), and reporting obligations to the authorities.

Divergent approaches between the European Union and the United States, complicating compliance management

A. Weakening of the PCLOB: What future for data transfers between the EU and the United States?

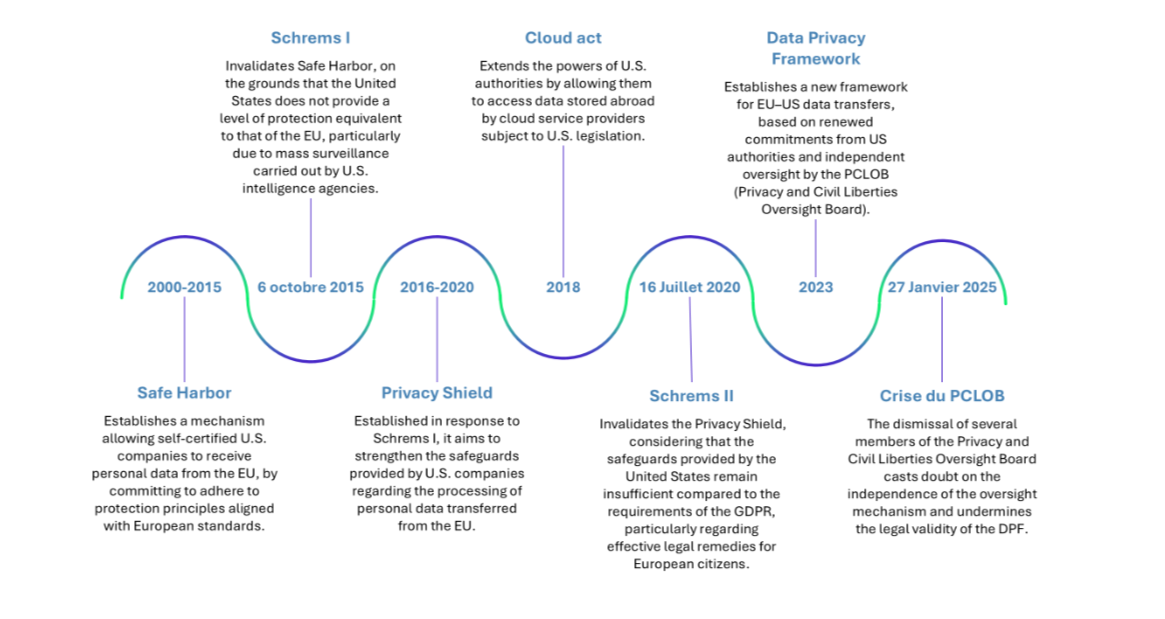

The agreements for the transfer of personal data between the EU and the United States have experienced several disruptions, marked by the Schrems I and Schrems II rulings, which successively invalidated the transatlantic agreements due to non-compliance with the requirements of the CJEU. Then, in 2023, the European Commission adopted the Data Privacy Framework (DPF), intended to re-establish a compliant legal framework, relying notably on the PCLOB, an independent body responsible for overseeing U.S. intelligence practices.

However, on January 27th, 2025, the Trump administration revoked several members of the PCLOB, rendering the body inoperative. This decision undermines the validity of the DPF, pushing companies to revert to Transfer Impact Assessments (TIA), which are complex, costly, and legally uncertain.

Historical Overview of EU-US Relations in Personal Data Transfers

An invalidation of the DPF would once again raise questions about the legal framework for personal data transfers between the EU and the United States. In this context of legal instability, a sustainable solution might emerge from technology rather than law. One such example could be homomorphic encryption, which, although not yet fully mature, represents a promising avenue for ensuring data security, provided that sovereign European solutions are developed.

B. Divergent Approaches to Regulating Artificial Intelligence

In recent years, artificial intelligence has experienced rapid growth, bringing with it new cybersecurity risks and threats. To address these challenges, the European Union and the United States have adopted opposing regulatory approaches.

The European Union has chosen to implement regulations to govern the development of artificial intelligence. The AI Act was adopted in May 2024, imposing security measures to be implemented according to the risk levels of the systems.

The United States, on the other hand, is focusing on a strategy centered on technological competitiveness and industrial sovereignty, with minimal regulation. This approach was formalized with Executive Order 14179 on January 23rd, 2025, titled “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence” This order mandates the development of an action plan to strengthen the United States’ dominant position in artificial intelligence. It also repeals measures deemed restrictive to innovation and aims to eliminate any ideological bias or social agenda in the development of AI systems.

In this context of strengthening regulations, what approach should be adopted to manage the accumulation of regulations?

The dynamic of strengthening international regulations contributes to a layering of multiple regulations, complicating compliance management, especially for companies with a significant international footprint. Faced with this complexity, two main approaches can be considered, depending on the context, organization, and international footprint of the companies.

Centralized Approach

The first approach is based on the development of a global framework of measures. This framework can be based on recognized international standards such as ISO/IEC 27001 or NIST CSF 2.0, or on a regulation deemed key and particularly comprehensive. All applicable regulations are then mapped to this framework, ensuring a cross-cutting coverage of obligations through a single standard.

The responsibility for implementing compliance measures is carried out by central or local teams, depending on the nature of the measures, with always strong control at the central level.

This approach is particularly suitable for companies with a centralized organization and information system, and with a limited international footprint.

Decentralized Approach

The second approach favors a decentralized organization of compliance, relying on local teams. In this framework, a global regulatory framework is defined at the central level, which constitutes a minimum compliance base for all regions. It generally covers 85 to 90% of the requirements of all regulations that can be found at the local level.

However, in this approach, the aim is not to complete the global framework based on the analysis of all local regulations. The responsibility for adjusting to local or regional requirements lies with local CISOs, who ensure compliance with local measures, particularly the 10 to 15% of measures not covered in the global framework. This organization allows for differentiated implementation according to regions, while maintaining a central normative framework.

This model is particularly suited to decentralized structures, characterized by strong local autonomy and an extensive international footprint. It offers greater agility in the face of regulatory changes, relying on a fine understanding of national contexts, while reducing the central management burden.

Practical Case of Supporting a Client with a Strong International Presence

A recently implemented cybersecurity program within an international group illustrates a decentralized approach with strong group control.

The compliance framework, defined by the headquarters, is based on security objectives founded on threat scenarios and relies on a common foundation integrating the main applicable regulations. This foundation is structured from a multi-framework matrix (DORA, NIS2, ISO 27001). Local entities ensure the operational deployment of the measures defined at the group level, as well as their internal control, under the coordination of a local CISO responsible for consolidating information and ensuring its reporting. The system also provides for local adjustment capabilities, allowing feedback on the central strategy, particularly to avoid potential contradictions with local regulations.

The group CISO plays a transversal supervisory role. They verify that the requirements defined at the central level are well taken into account by the local CISOs, even though the latter are responsible for their implementation. They also ensure that the deployed systems are aligned with both group requirements and local regulations. Their role is not to challenge local choices but to verify their coherence with the global framework.

In terms of control governance, each regulatory requirement, whether local or group-originated, is associated with a specific control. Clear governance between the group and local levels is therefore essential to manage a coherent control catalog, avoid redundancies, and ensure good articulation in the compliance system.

This model ensures a homogeneous security foundation while preserving the flexibility needed to adapt to local regulations. However, it also has certain limitations. Its centralized structure, while ensuring overall coherence, introduces some complexity in daily management, particularly when it comes to evolving the system or quickly integrating new regulatory requirements.

Possibility of Decoupling Information Systems

Beyond these approaches, some companies choose to decouple their information systems. This decision is made in a context where geopolitical tensions increasingly influence cybersecurity strategies. In this context, the growing importance of sovereignty and protectionism in cybersecurity regulations creates contradictions between regulations, making it difficult, if not impossible, to ensure the compliance of a single information system with regulations from different geographic areas.

Decoupling addresses these issues by providing dedicated infrastructures, applications, and teams for different geographic areas, typically the US, EU, and Asia, with strict filtering between zones.

Towards a Phase of Consolidation and Rationalization?

In this context, we seem to be heading towards a phase of regulatory consolidation, with the implementation of recently adopted texts and a slowdown in the publication of new regulations. However, developments could still occur to consider the emergence of new technologies, particularly quantum computing.

Moreover, in the face of increasing regulatory complexity in the EU, the European Commission seems to be initiating a new phase of rationalization, aiming to lighten certain obligations deemed unsuitable. This desire for rationalization is notably reflected in a targeted project to ease GDPR requirements for SMEs.

Another avenue for simplification involves the establishment of mutual recognition mechanisms between regulations in different countries. Regulatory compliance for companies could then be simplified, provided that states explicitly integrate this logic into their national regulations. France, for example, is considering integrating this mechanism into the bill on the resilience of critical infrastructures and the strengthening of cybersecurity. However, mutual recognition could lead to a risk of regulatory dumping: some companies might choose the least stringent frameworks to reduce the cost and complexity of compliance, to the detriment of security.

This principle is not entirely new: the GDPR already recognizes third countries as having an “adequate” level of protection (e.g., Japan, Canada, Argentina), thus facilitating data transfers with these countries.

[1] https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-cybersecurity-outlook-2025/