Audits and Red Team assessments led by Wavestone showed a stark imbalance between the maturity of on-premise infrastructure protection and the cloud deployment ones. While on-premise infrastructure are generally well identified, controlled and protected according to proven standards, their cloud counterparts are often underestimated in terms of risks and consequently, insufficiently secured.

Is the tiering principle promoted for on-premise infrastructure applicable to the cloud?

Evolution of the Security Model

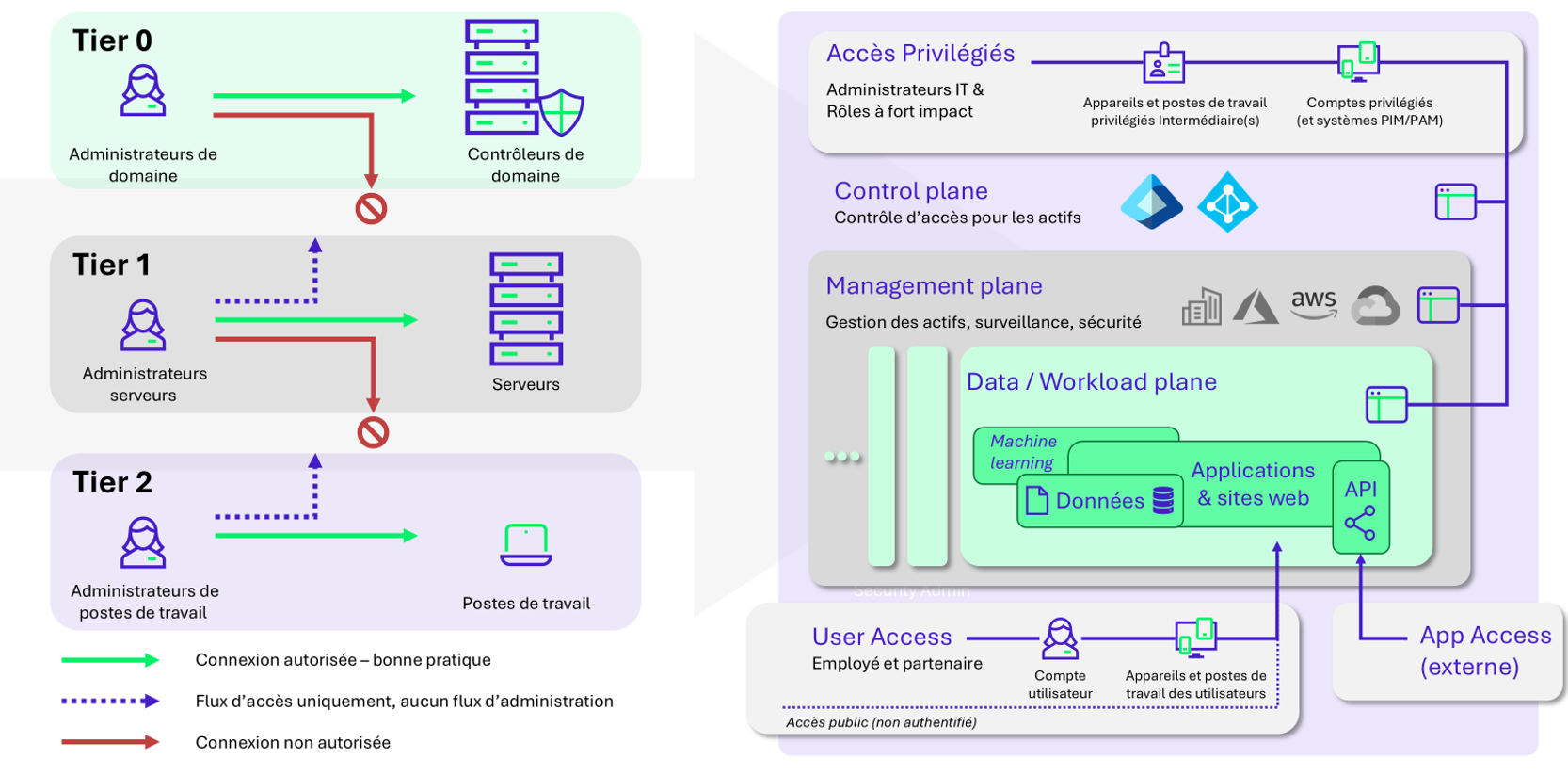

In on-premises Active Directory environments, infrastructure security generally relies on strict segmentation into three tiers (T0, T1, and T2). This allows for the isolation of critical administration systems (T0), servers (T1), and user workstations (T2) in order to limit propagation risks.

This hierarchical and perimeter-based organization is inherent to the AD world and cannot be directly applied to the cloud for the following two main reasons:

- Portals are centralized: A wide variety of administrators with different rights.

- The boundary between administration levels is more complex: The principle of granular permissions, whether Role-Based (RBAC), Attribute-Based (ABAC), or conditional (location, risk, compliance, authentication methods, etc.) allows for very precise access configuration, but it complicates and obscures the global view of permissions.

To address this new paradigm, Microsoft published its Enterprise Access Model (described here), highlighting three main planes: the Control Plane, Management Plane, and Data Plane.

This model retains “cascading” criticality but simplifies it with:

- the 3 tiers into 2 access types: administrator vs. user;

- the administration flows into portal access;

- the server’s criticality is centralized within the Data plane.

Below is a comparative illustration between the old and the new model:

This new model particularly highlights 3 elements:

- User identity: privileged access vs. user access;

- Data and services: at the expense of servers;

- The method of access to web administration portals.

The inversion of importance between “servers” and “web portals” abstracting Active Directory is a radical change.

However, very few (if any) large organizations are at this stage of abandoning their “legacy” IS; a large part will be in a transitional state where the information system has been virtualized on a cloud in order to move away from its datacenters, but whose administration methods have remained the same.

These companies must deal with an obsolete tiering model and an Enterprise Access Model disconnected from current security risks and needs.

For the remainder of this article, we will take as an example the Tartampion company, which has just completed a 3-year Move-to-Cloud program on AWS. The outcome is as follows:

- A Landing Zone was created, applications already on AWS were integrated into it

- Given the lack of time and resources, a major part of the IS was incorporated via lift and shift, including business, network, bastion, and AD solutions.

- The Data Centers were closed

A problematic hybrid and virtualized IS

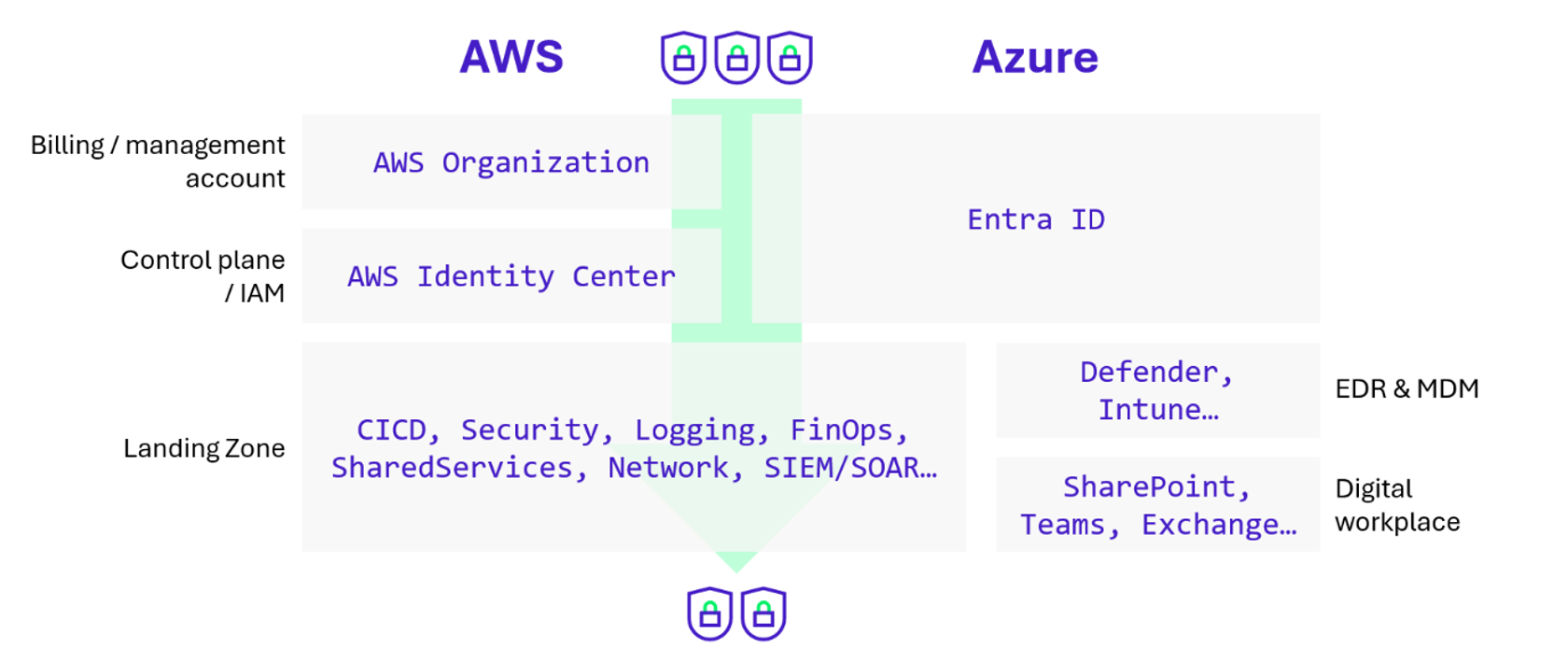

According to the EAM, Azure and AWS portals are displayed at the same level (the management plane) at the T1 tier, without any other form of distinction. However, these 2 cloud environments are in themselves the support for numerous IS, used by multiple collaborators with very varied levels of rights and impacts.

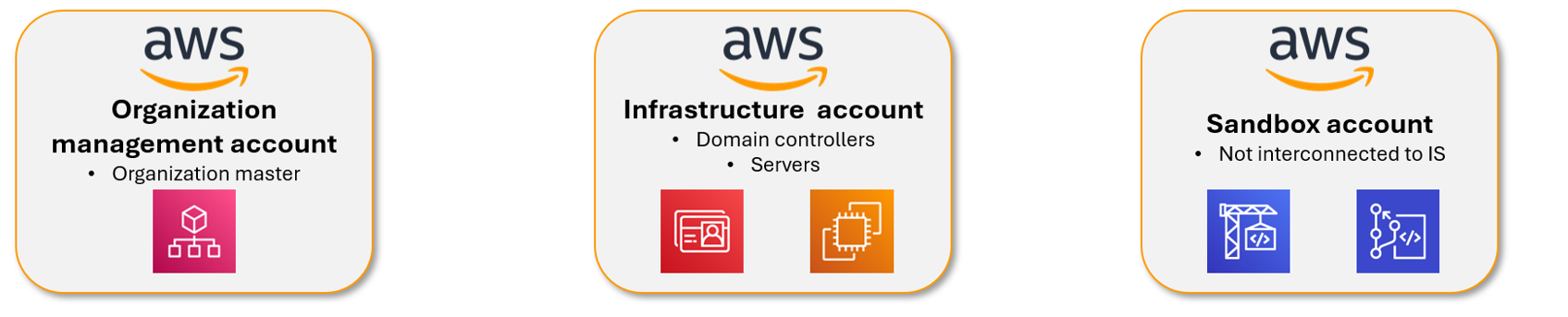

To illustrate the previous points, let us set aside the Digital Workplace aspect (O365 suite) and take 3 AWS accounts from a Tartampion Landing Zone, supporting different infrastructure services:

Based on the framework proposed by Microsoft, these three AWS accounts should belong to the Management plane with a T1 security level. However, in the event of a compromise of one of the 3 accounts by an attacker, the impacts would be very different.

If the Landing Zone is correctly implemented, the compromise of a Sandbox account would have very little impact, whereas that of the Master Account would lead to the compromise of all underlying accounts and resources.

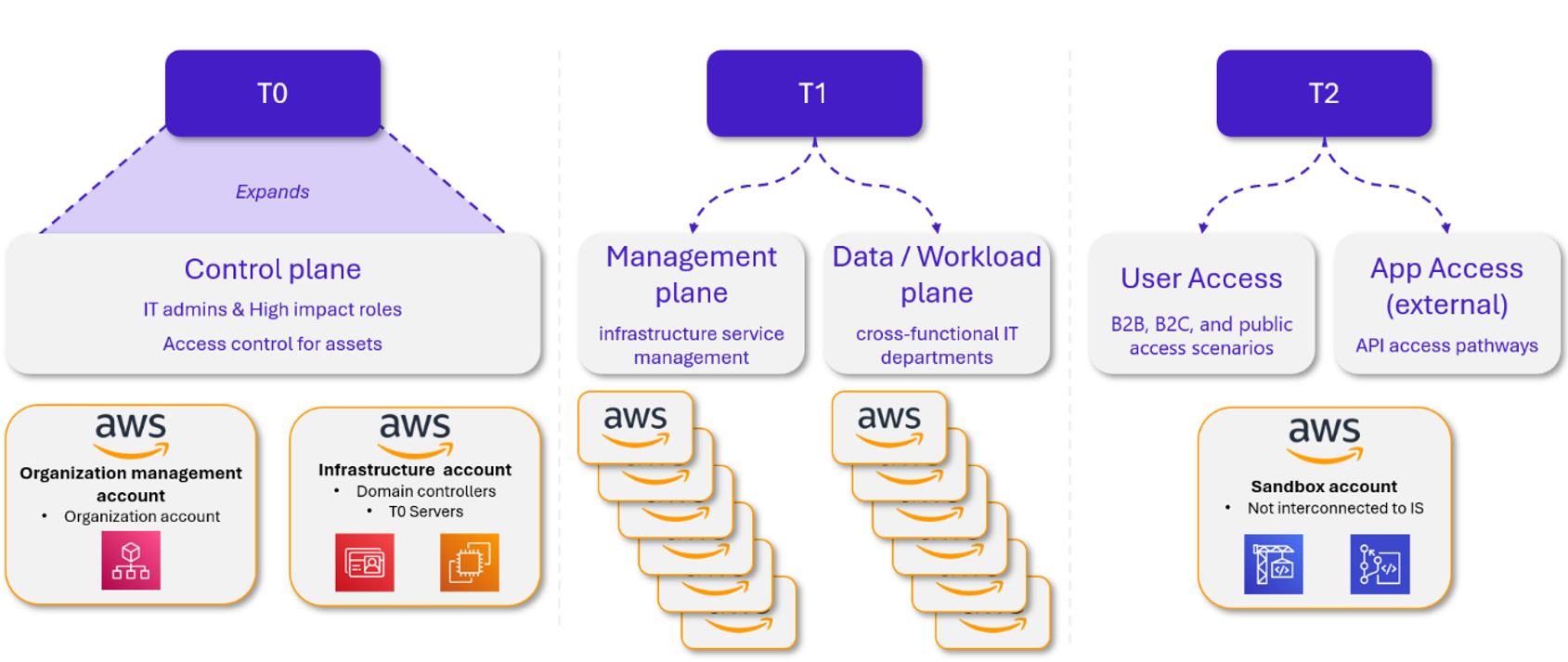

A more adequate example of segmentation would be the following:

Microsoft’s Enterprise Access Model is a macroscopic framework that allows for initiating a baseline for cloud service segmentation, but which remains to be adapted according to the criticality of the concerned IS.

How can it be made relevant? To answer this, it is necessary to understand the attack scenarios exploiting cloud services.

The cloud from an attacker’s perspective

5 cloud principles facilitating attacks

Firstly, public cloud administration panels are exposed to the Internet by default, unlike sensitive IS resources. Thus, successful phishing very likely leads to access to the cloud.

Secondly, companies today have hybrid organizations (on-premise and cloud):

- Cloud infrastructures are connected to the rest of the on-premises IS;

- Workstations can also be hybrid and managed by a cloud service like Intune. Permissions to use this service are managed in Entra ID;

- Identities are often synchronized accounts, this also applies to administration accounts.

Hybrid organizations can facilitate lateral movement between the cloud and on-premise environments.

Thirdly, identity management is very complex with different scopes. For example, Entra ID allows managing access to Azure and M365 for users, as well as for applications and service accounts.

In addition, cybersecurity concepts related to the cloud are still relatively new and unfamiliar to certain “legacy” teams, such as the SOC/CERT, network, etc. The most sensitive cloud resources are not systematically identified, protected, and monitored.

Finally, even if native detection mechanisms are present, they are not always interconnected with SIEM/SOAR, which slows down response capabilities. Moreover, a recent Purple Team operation conducted on Azure and AWS infrastructure confirmed that native detection tools have limited detection capacity. This is an observation also found in Red Teams since, with an “OpSec” approach, cloud detection tools are rarely able to identify an ongoing attack.

Feedback from our penetration tests & Red Team

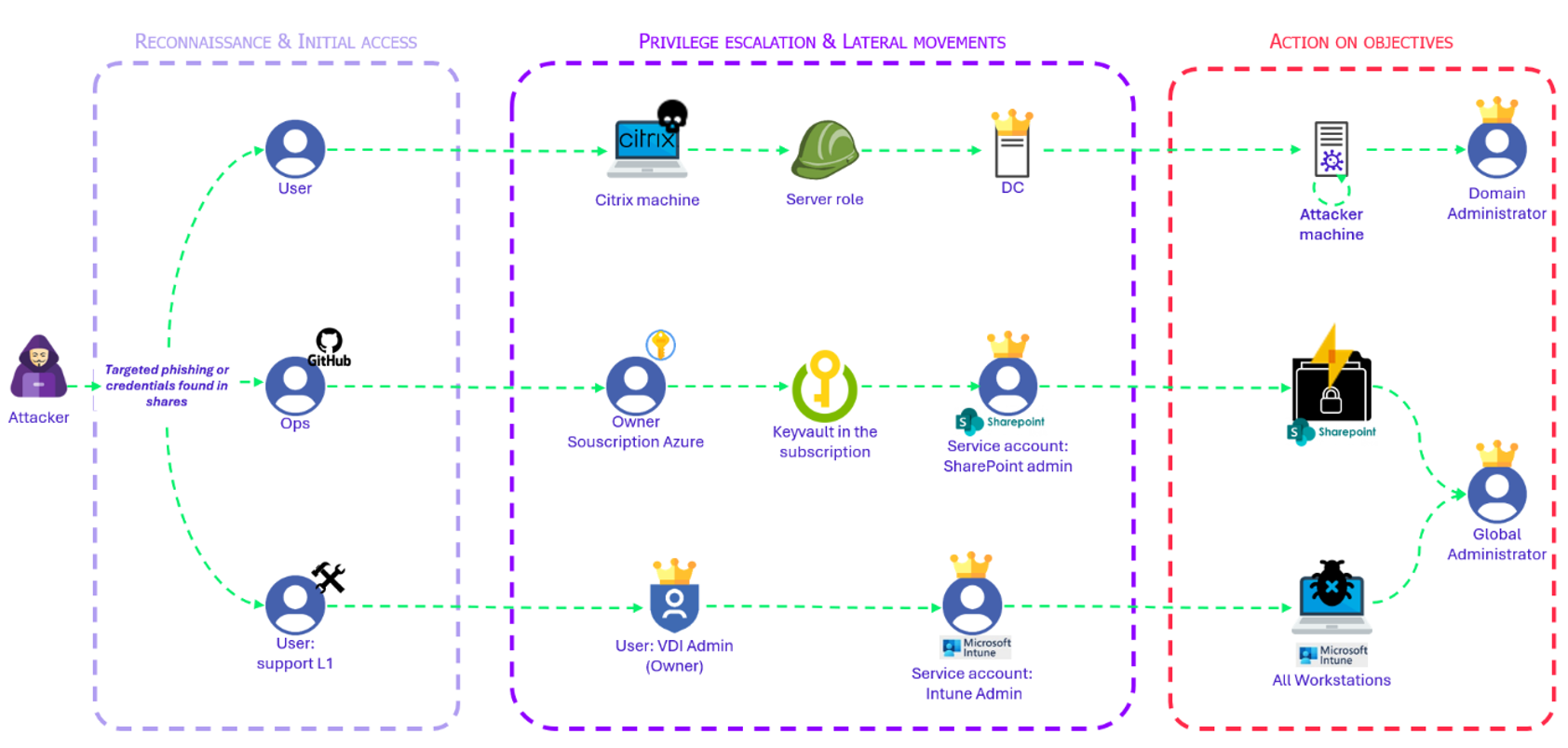

Derived from recent Red Team operations, these cloud-specific attack paths demonstrate the impact and the ease with which it is possible to escalate privileges to obtain highly permissive access:

The first scenario, carried out on AWS, is described below; the other two were analyzed in a series of Risk Insight articles available here.

Reconnaissance and Initial Access

Categories of employees are generally targeted in order to compromise a person with interesting rights in the IS (Developer, Support, OPS…). A frequently used method is phishing. Current phishing mechanisms can bypass the use of complex passwords and most MFA (Multi-Factor Authentication) methods.

Privilege Escalation and Lateral Movements

In the first scenario, a compromised developer possessed access to a Citrix farm. Citrix environments are not simple to completely harden, and a few breakout vulnerabilities allowed the Red Team to gain access to the underlying server.

Information gathered on the machine indicated that the server could be hosted on AWS. This was verified by trying to access the server’s AWS metadata: the instance had rights on the client’s AWS account. The Citrix virtual machine possessed the “AmazonEC2FullAccess” role allowing it management actions on EC2s in the same AWS account.

Using the AWS CLI, the other EC2s were listed. A Domain Controller was present in this AWS account. It is a common practice to regroup services intended to be used by several projects into a single account, generally called “Shared Services”. It is nevertheless recommended to verify that the criticality of shared services is homogeneous to be able to apply adequate hardening on the account or separate them into several environments.

Actions on trophies

From the Citrix server AWS role, a snapshot of the domain controller was taken and then downloaded. Domain controller backups contain all the machine’s files, including the most sensitive files like the ntds.dit database, which contains the information and secrets of all domain users. The exfiltration of this database translates to the total compromise of the concerned AD domain.

This scenario illustrates one of the attack paths that were exploited during Red Team operations, facilitated by the lack of visibility regarding the impacts that a compromised resource hosted on the cloud can have.

Faster and stronger impacts

Attacks already possible on an on-premises IS can be reproduced and even accelerated thanks to cloud features. For example, the encryption of S3 buckets (file storage service) using a KMS (encryption) key from another AWS account mimics massive data encryption, or the use of the “lifecycle” feature allows for the deletion of all objects in less than 24 hours, regardless of the amount of data.

New attacks have also appeared, such as “Subscription Hijacking” which allows transferring an Azure organization’s subscription to another and thus stealing all the data it contains while preventing remediation actions. This attack is achievable in a few clicks from the Azure web interface.

Identification and protection of the cloud trust core

Identification

The trust core adopts an approach focused on asset prioritization, which differs from the tiering model or Microsoft’s Enterprise Access Model. Unlike these models which offer a predefined segmentation, there is no universal grid: each organization must identify for itself which resources deserve the highest level of protection. The idea is to establish a restricted circle of critical resources (whether cloud or on premises) and then deploy decreasing levels of protection as one moves away from this core.

The identification of the trust core relies on two main criteria:

- Business Criticality: these are the resources that concentrate the value and business continuity of the company. If they were to be lost or compromised, the consequences would be immediate for daily operations and financially. A SharePoint environment containing intellectual property / patents is a common example;

- IS Criticality: these are the resources that ensure the administration of the information system and which possess a high level of access. Their compromise would have a major impact on the entire IS and would allow for the business impact previously mentioned. Here we find domain controllers or cloud IAM services like Entra ID and AWS Identity Center.

This mapping is never totally clear-cut. For certain elements, the posture to adopt remains vague; two examples illustrate this well:

- EDR: an obvious security element of an IS, systematically deployed on both workstations and cloud and on-premises servers, its administration console is increasingly exposed to the internet, and allows executing arbitrary commands on the devices equipped with it.

- CI/CD pipelines: a clever but complex agglomeration of applications calling each other, whose access (the code repository: GitLab, GitHub…) is accessible by all collaborators and the runner permissions are very often administrator over the entire cloud infrastructure. Out of all Red Teams conducted in 2024 & 2025, 80% exploited vulnerabilities associated with these solutions to progress in their operation or even obtain compromise trophies through these means.

In order to identify the center of the trust core, which we will call the security foundation, we can revisit the precepts of the old T0: the compromise of one of its elements would probably lead to that of the others, and by cascade, of the major part of the IS.

Assuming that your applications apply correct inter-user segregation (all of your SharePoint sites are not accessible by everyone, are they?), references to the next applications should be understood as administrator / super-user access to them, and not simple user.

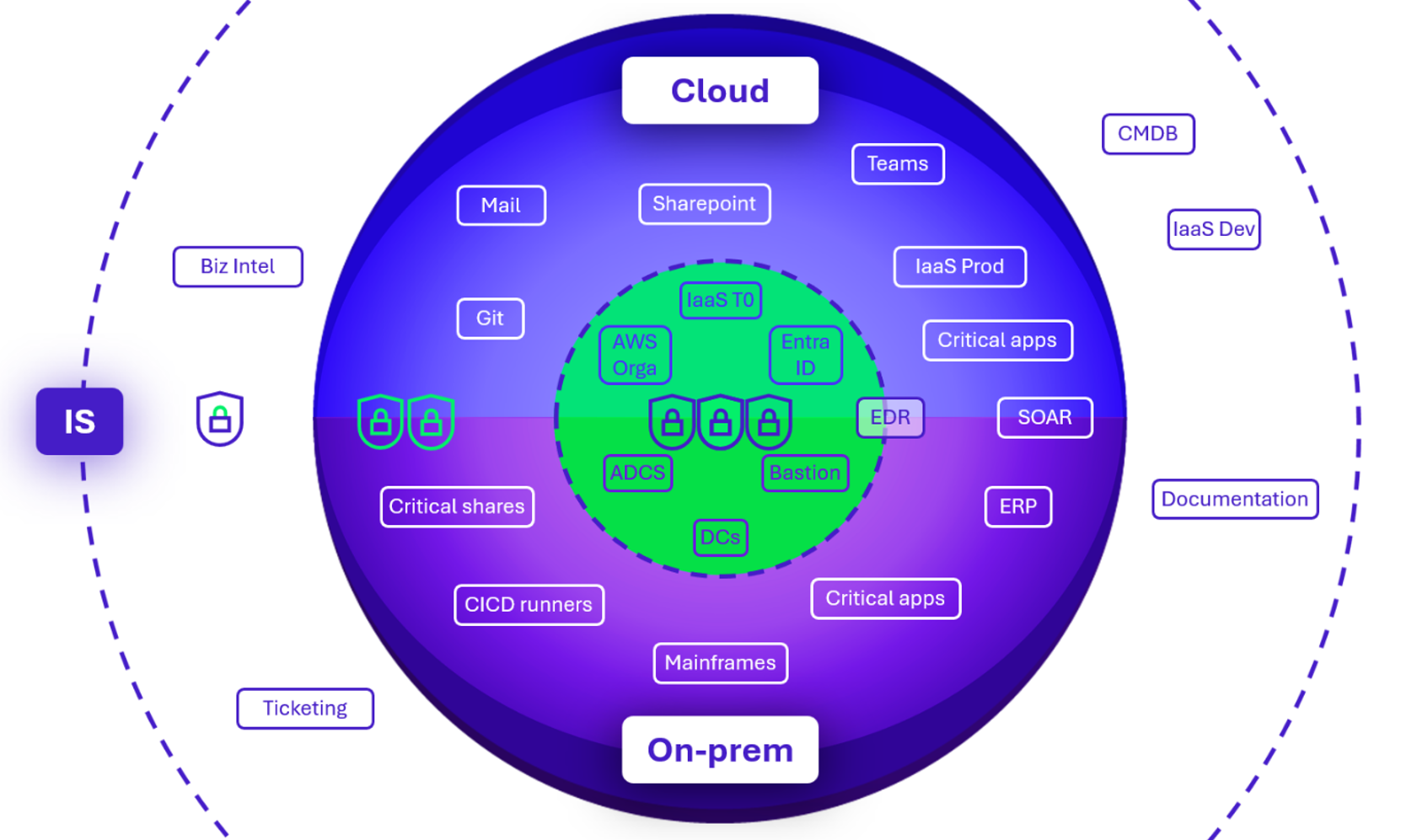

Here is one possible representation of a hybrid trust core:

In this representation, on the on-premise side, we can observe:

- The T0, with its domain controllers, ADCS, and potentially the PKI, the bastion, the EDR console…

- The T1, integrating additionally high-impact business applications.

And on the cloud side, we find:

- At the core, the Control Plane (AWS Orga & Identity Center, Entra ID) as well as the Landing Zone modules supporting T0 (if part of T0 is hosted in the cloud);

- Moving outward, the various administration consoles for productivity suites, and for infrastructure or application management.

When establishing this diagram, it is important to keep in mind that:

- IT serves the business, and even though the central zone of the trust core is mainly occupied by technical components, critical solutions should be included;

- Dependency/compromise chains have a significant impact on architectural choices: positioning an AD on AWS, or deploying an EDR on an AD can suddenly create numerous paths for compromise and pivoting between the 2 worlds.

Finally, building a trust core cannot be limited to a static classification logic. It must rely on an approach that evaluates the criticality of each asset and the risk it introduces (a software development company will surely not position its Git at the same level as a civil engineering company).

Protection of the cloud trust core

The security of the trust core will rely on the two traditional risk factors:

- Reduce impact: How to prevent a compromised or malicious user from connecting to cloud portals via a browser and performing sensitive actions in a few clicks, such as backing up a domain controller hosted on a VM or deleting production data backups?

- Reduce probability: How to reduce the risks of illegitimate access from a session cookie stolen via phishing, workstation compromising, or user password reuse?

Protection of the cloud security foundation

Regarding the cloud “security foundation,” it is possible to prioritize environments by criticality according to this macroscopic scale:

Depending on the teams involved and the complexity of including them in a particularly high protection level, some organizations choose to exclude environments whose compromise would not allow for dangerous lateral movement, such as those for FinOps, detection, the Digital Workplace…

Securing the cloud security foundation relies on 2 main points:

- Impeccable hygiene: streamlined IAM configuration, least privilege strategy, deployment procedures, limitation of resources to the strict minimum…

- A passive / active security layer: deployment of policies (SCP on AWS, Policy on Azure) explicitly forbidding certain actions, or the manipulation of certain resources, and detection rules to trigger an alert in the event of a policy modification or the occurrence of one of its protected events.

These policies can be effectively associated with a tagging strategy to apply, in addition to the RBAC (Role Based Access Control) model, an ABAC (Attribute Based Access Control) model.

For example, it is possible to tag different resources with a “tiering” key and a value between “T0”, “T1”, “T2” and then deploy this set of strategies:

- Prohibit any action targeting a resource tagged “tiering” by an identity whose own tiering tag value is not equivalent;

- Prohibit the manipulation of tiering tags, except for a specific role.

And that is how, with a few tags and 2 SCPs, it is possible to replicate the Microsoft tiering model (some exceptions may occur).

Protection of identities and access

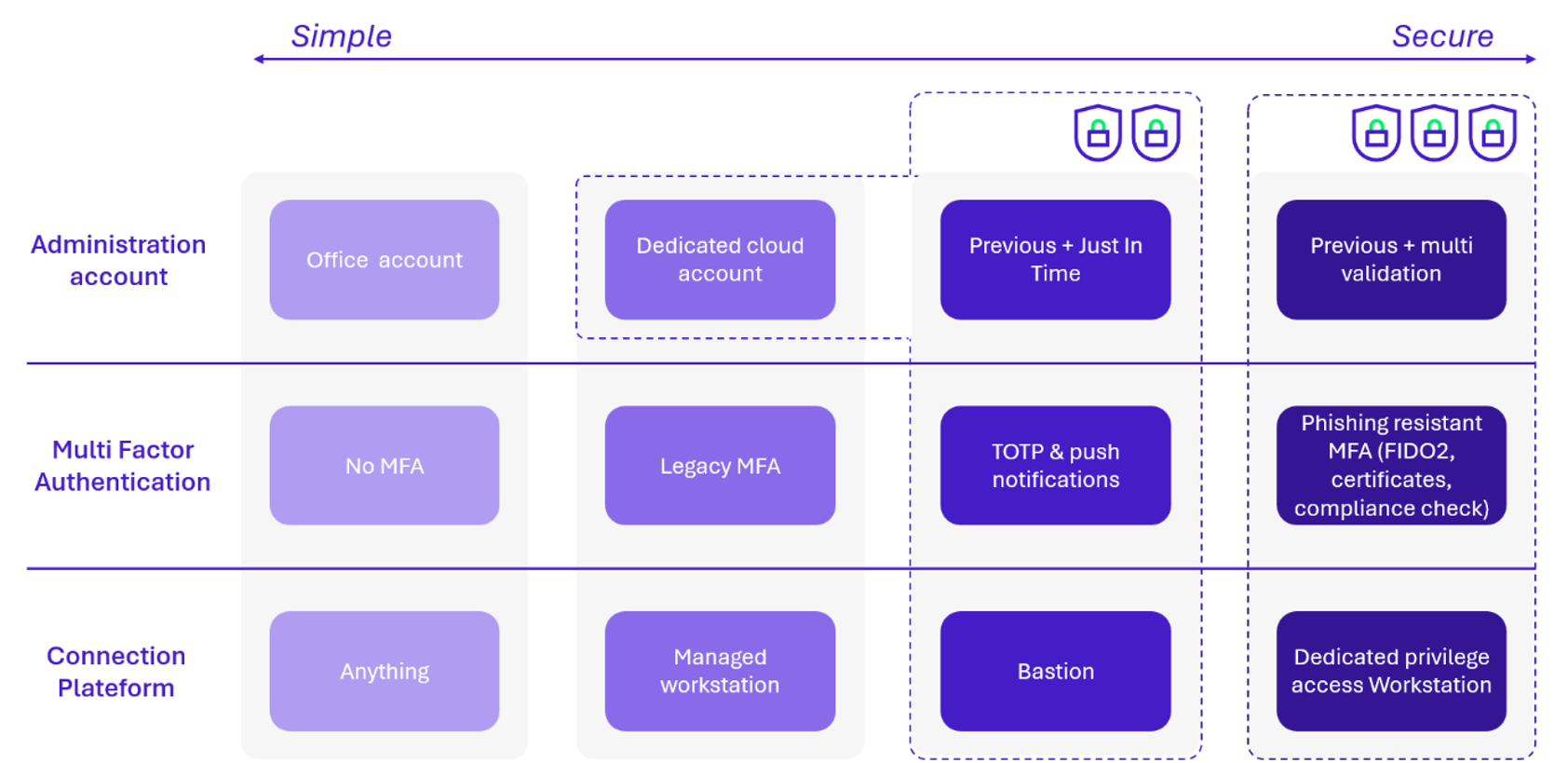

To protect users, 3 hardening themes can be implemented:

- Identity: With which account does the user connect to cloud administration interfaces? How are rights obtained?

- MFA: Is the identity protected with multi-factor authentication resistant to phishing attacks?

- Origin: From which platform does the user connect to cloud administration interfaces? Is the platform managed, and healthy?

Several levels of protection are conceivable in order to protect cloud administrators:

To protect the restricted trust core, represented by the triple padlocks, it is recommended to implement the most robust authentication factors. This includes the use of a dedicated account for cloud administration, the activation of physical multi-factor authentication (example: FIDO2 security key), and the use of a workstation specifically reserved for operations on this trust core (this last one is not often implemented).

For resources further from the center of the core of trust, symbolized by the double padlocks, a hardened but proportionate security level can be applied, in order to strengthen protection to control costs and reduce excessive constraints on the users concerned.

Ultimately, the most secure methods are also those that imply the most constraints for the people concerned, usage must be controlled (limiting day-to-day operations) and emergency situations considered.

Repeat Operations

At the end of the identification and protection phases, resources will be distributed across the different layers of the core of trust.

To verify the proper implementation of the core of trust, an audit can be conducted to verify the proper protection of the critical resources that compose it.

An information system is always evolving, but the first two phases will have been performed at a given moment. New critical resources may be added, others modified or even deleted. It is essential to regularly re-evaluate the IS and update the distribution of resources within the core of trust.

In conclusion, information system security now operates within a context of increasing complexity and strong diversification of infrastructure components and services.

In this context, it appears increasingly complex to define a universal security model. Certain frameworks retain all their relevance within well-identified perimeters: tiering remains a reference for securing Active Directory, just like the EAM for cloud environments strongly centered on the Microsoft ecosystem. Nevertheless, these models quickly reach their limits as soon as one moves away from these specific use cases.

For the majority of information systems, an approach based on risk analysis therefore stands out as the most relevant. Identifying a core of trust, clearly defining critical assets – the crown jewels – and deriving security measures from these elements allow for building a more pragmatic security posture, adapted to the reality of the IS and capable of evolving with it. This logic, less normative but more contextualized, undoubtedly constitutes one of the major levers for reconciling security, agility, and sustainability of information systems.