In a highly interconnected industrial environment, operational performance relies on an extended ecosystem of partners: critical suppliers, system integrators, maintenance providers, software vendors, IT and OT service providers, and others. While this ecosystem is essential to the company’s operations, it also represents one of the primary vectors of cyber risk.

Cyberattacks no longer target only internal information systems. They increasingly exploit external dependencies, where governance, visibility, and control are often weaker. A vulnerability affecting a third party can now lead to direct impacts on production, personnel safety, regulatory compliance, or the organization’s reputation.

The attack suffered by Jaguar Land Rover in 2025 illustrates this reality: the shutdown of systems paralyzed the production chain and its partners, preventing the manufacture of more than 25,000 vehicles and resulting in estimated losses of nearly one billion pounds.

Managing third-party cyber risks is therefore no longer a peripheral issue. It is a central component of any industrial cybersecurity strategy, commonly referred to as TPRM (Third-Party Risk Management) or TPCRM (Third-party Cyber Risk Management). These concepts cover the overall management of third-party risks and its specific application to cyber risks.

Third parties driving the industrial value chain

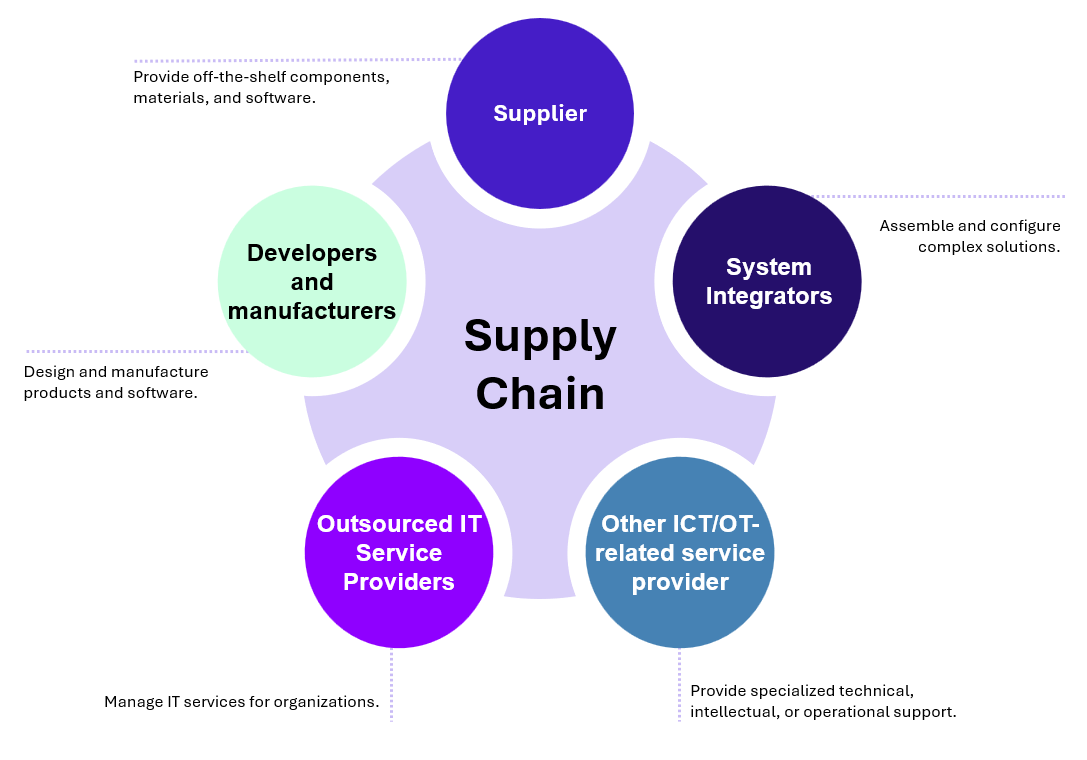

The concept of a “third-party” refers to any external entity or individual that collaborates with an organization and interacts with its systems, data, or processes. These actors contribute directly or indirectly to the company’s activities and collectively form what is known as the supply chain.

In industrial environments, third parties can generally be grouped into five major categories, reflecting the diversity of roles they play in the operation and maintenance of industrial systems:

Mapping third parties across the supply chain

To ensure seamless operational continuity, industrial organizations rely heavily on external service providers. This dependency, driven by the outsourcing of critical activities and regulatory requirements, turns each supplier into an essential link in the chain. A single compromise affecting a third-party can be enough to halt production, disrupt operations, and expose the organization to major risks.

An extended supply chain: difficult to manage and vulnerable

The diversity and number of third parties present several major challenges for organizations. First, the third-party ecosystem is often extremely large: a single organization may rely on hundreds or even thousands of partners.

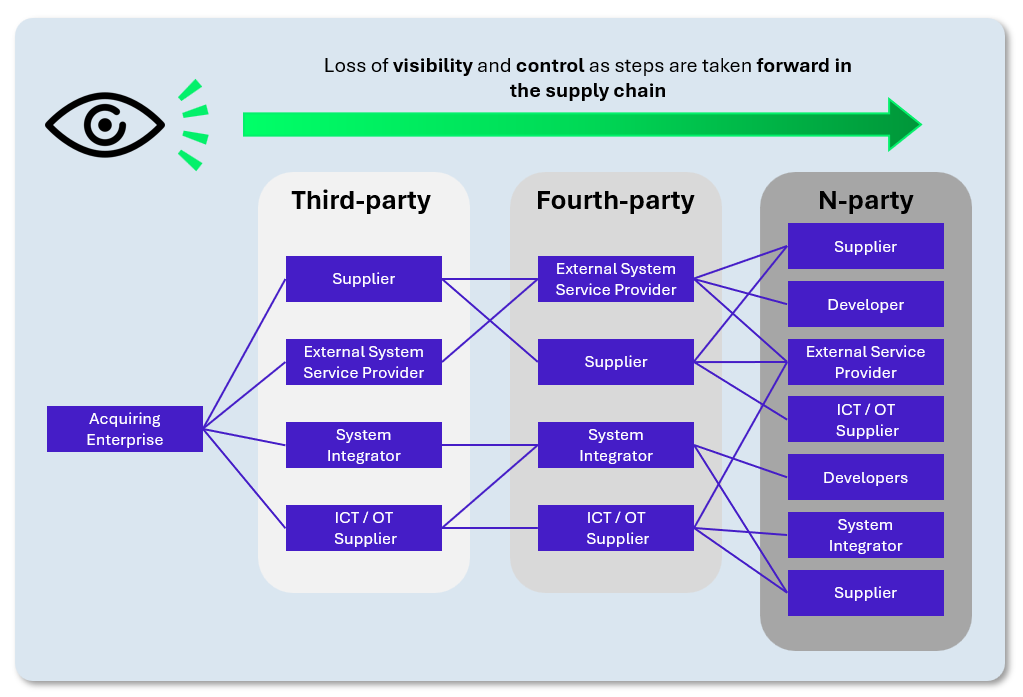

This scale is compounded by significant complexity, as the supply chain does not stop with direct third parties, but also includes their own service providers, which are essential to their business continuity. As one moves down these successive levels (fourth parties, n-parties and beyond), the client organization’s visibility into its third parties decreases sharply:

An illustration of supply chain complexity

An illustration of supply chain complexity

This combination of breadth and depth makes it particularly difficult to maintain overall control of the ecosystem. For example, it is estimated that only 3% of organizations have full visibility across their entire supply chain (Panorays, 2025). This lack of visibility creates a broad and difficult-to-manage risk surface.

Third party risks: a growing threat under regulatory pressure

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in cyberattacks involving third parties. This trend is particularly pronounced in industrial environments, where third parties are often involved in critical and vulnerable processes: remote access to systems, physical access on site, identity and access management, and the integration of software or hardware components.

These figures highlight two key observations. First, third-party risks are very real and represent a growing threat to the cybersecurity ecosystem. Second, the maturity level of organizations remains globally insufficient, even as TPCRM emerges as a strategic lever for risk reduction.

These figures highlight two key observations. First, third-party risks are very real and represent a growing threat to the cybersecurity ecosystem. Second, the maturity level of organizations remains globally insufficient, even as TPCRM emerges as a strategic lever for risk reduction.

These findings are now reflected in regulatory frameworks. The European NIS 2 Directive, currently being transposed into national laws across EU Member States, requires affected organizations to manage risks related to their supply chains. Managing cyber risks linked to third parties is thus becoming a full-fledged regulatory requirement, with potential penalties of up to €10 million or 2% of global annual turnover in the event of non-compliance.

Adapting third party risk management to industrial needs

In light of these challenges, how can organizations structure effective third-party cyber risk management? While approaches vary, several key principles consistently emerge:

- Cross-functional stakeholder involvement: Third-party risk management cannot be the sole responsibility of IT or cybersecurity teams. Procurement, operational teams, and business units must be fully involved, as third parties operate across all levels of the organization.

- Lifecycle-based approach: Risk must be considered from supplier selection through to the end of the commercial relationship. Each phase (contracting, onboarding, operations, and offboarding) should be governed by appropriate security requirements.

- Clear contractual requirements: Contracts should formally define and include explicit cybersecurity obligations to ensure a consistent level of protection throughout the collaboration.

- Third-party prioritization: Security efforts must be proportional to the criticality of partners (e.g., level of system integration, operational dependency, sensitivity of exchanged data, relationship history). Assessing their operational role and cyber maturity helps focus resources on the most critical third parties.

- Collaboration and information sharing: Supply chain resilience depends on the ability of stakeholders to share information and coordinate responses in the event of an incident.

- Tooling and automation: Given the volume of third-parties, automation, continuous assessment, and the use of specialized tools are becoming essential enablers.

To support organizations in this approach, several authoritative references exist, including NIST SP 800-161 Rev. 1 “Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Systems and Organizations” (2022) and ENISA’s “Good Practices for Supply Chain Cybersecurity” (2023).

TPCRM: strengthening industrial resilience

In an industrial context where cyber risks are becoming systemic, supply chain security can no longer be addressed through a purely technical lens. It is now a strategic issue of governance and resilience.

A mature TPCRM approach not only supports regulatory compliance but, more importantly, enables organizations to better anticipate crisis scenarios, limit operational impacts, and strengthen trust across their partner ecosystem.

By combining governance, processes, technologies, and collaboration with the wider ecosystem, TPCRM establishes itself as a key strategic lever for sustainably securing industrial environments.