Preparing for crisis management is now necessary for most companies and large organizations. Conscious of the risk or driven by regulations (the DORA regulation is a good example), crisis exercises and simulations have become an unmissable annual event.

Even if the depth and complexity of these exercises vary, the capabilities tested are often the same. They almost always entail knowing how to take on roles, assimilate a strong flow of information (stimuli), and understand a high-stakes, high-intensity situation. These exercises train coordination and impact assessment, but they cannot be considered an end in themselves. Resolving a crisis is not limited to the famous: “isolate, cut, communicate, we’re out of the woods”. We are calling for a paradigm shift in the preparation of cyber crisis management.

Shift the focus from information management to feasibility

Most crisis exercises used today test the players’ ability to manage and synthesize the flow of information. However, this is not where the quality of crisis management is concentrated. Some might even say that a decision-making unit should not be in a situation where it is erratically and incessantly solicited by its stakeholders. A decision-making unit must be put in a position to decide. To do so, it must respect a healthy work rhythm in cooperation with other more operational bodies.

These exercises too often lead players, who are sucked into the time-consuming management of information, to take misleading operational sides. They make assumptions about what they can do and when – the famous “isolate, cut, communicate, we’re out of the woods.” These exercises give decision-making teams the impression that they are ready to cope when in fact they have limited their preparation to the ability to understand and coordinate events. This is a necessary step, but not sufficient.

The key word for a 2023 preparedness strategy? Feasibility. Notably, though, the feasibility of all the steps of crisis management is based on a wider spectrum than just information management. This feasibility must be measurable, specific, and enabled by documentation, equipment, simulation, and sequencing of these capabilities.

Preparing across the spectrum: from threat detection to reconstruction

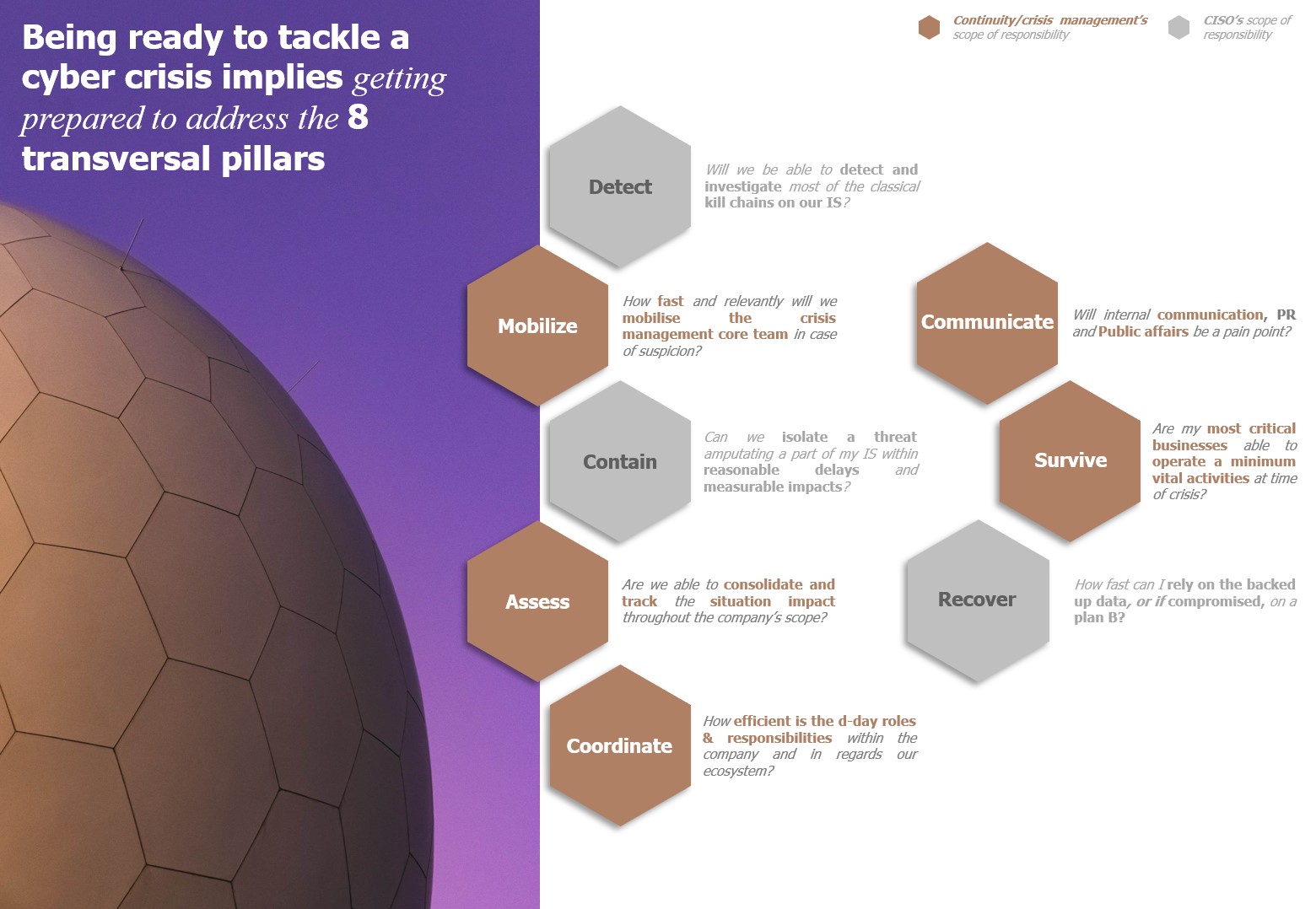

Training to manage a crisis involves above all taking into account the complete chronology of crisis management. We can summarize this chronology in eight major steps:

- Detect relevant threats and have the capacity to investigate them

- Mobilize experts and decision-makers to react

- Survive during the first peak by guaranteeing business continuity capabilities

- Evaluate the impact, its ramifications, and its foreseeable evolutions

- Contain the threat and understand the impact of isolation

- Coordinate your strengths and those of your ecosystem

- Communicate with internal and external stakeholders

- Restore and rebuild what can be restored and built when it can be restored and built

Also, prepare the tools: I design, I use

A relevant preparedness strategy must encompass each of these eight steps with the keyword of feasibility. It requires answering the question: will we really be able to carry out these actions when we need to?

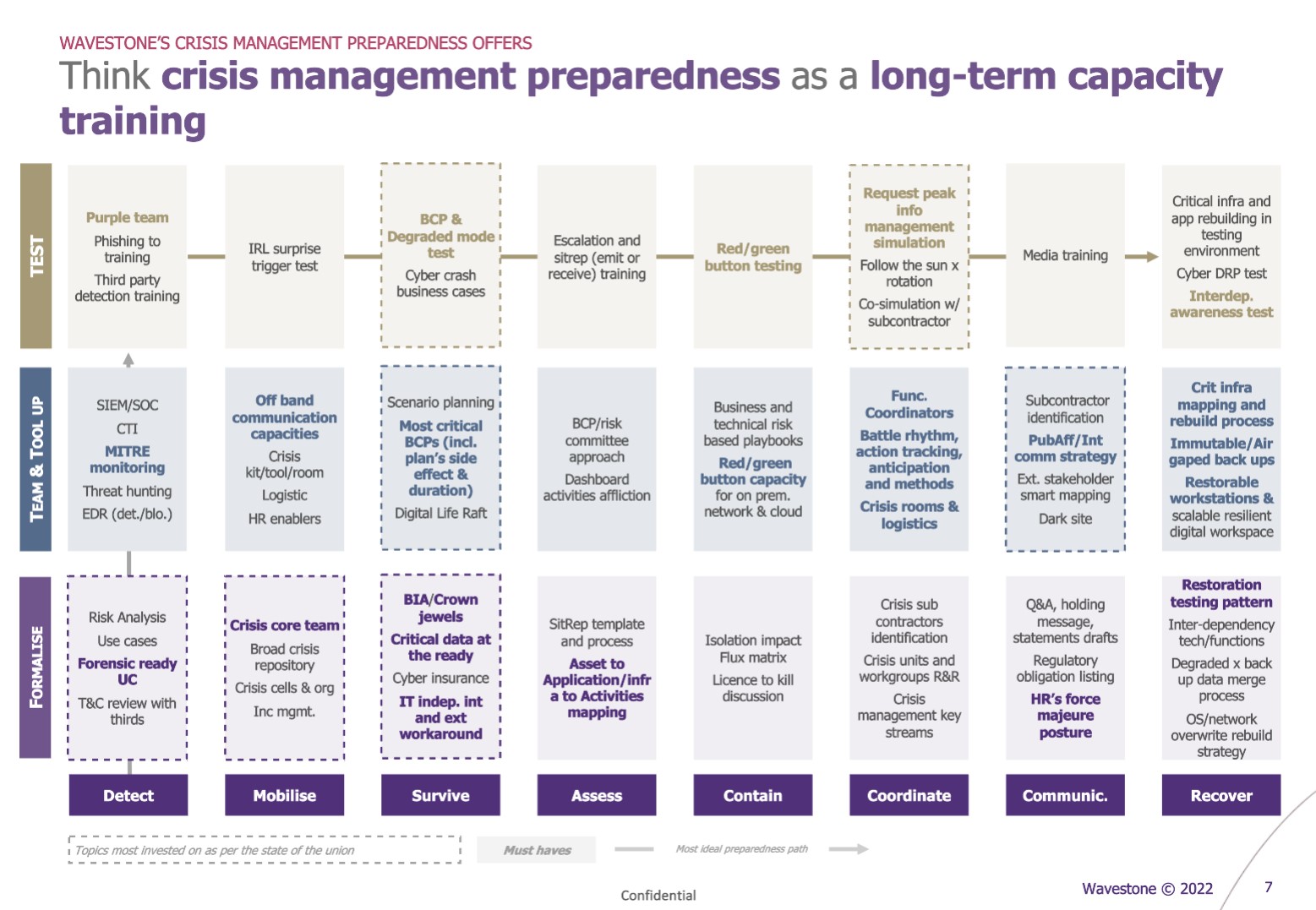

The answer to this capability question is based on three aspects:

- Ensuring the formalization of brief, up-to-date and known processes (e.g.: have a flow matrix indicating how to isolate, the timeframe, and the operational consequences)

- Equipping, training, and empowering the teams in charge of these actions (e.g.: having a discussion on “license to kill” and technically enabling a “red button” on relevant perimeters)

- Training the teams concerned specifically through role-playing exercises and specific simulations of the deployment of these capabilities (e.g.: test the decision-making process leading to the use of this “red button”, then technically test the proper functioning of the red button)

Thus, while some may limit themselves exclusively to the latter (simulation), it is essential to design one’s preparation with more hindsight and to begin with a real effort to build capacity. The exercise should be a milestone for verifying, adjusting, and promoting capabilities. In the worst case, it can be a deadline for preparing the capability or even serve as an opportunity to build said capability during the session (e.g.: reconstruction chronology, identification of technical interdependencies, etc.).

Overcome opportunistic logic and practice the capabilities’ sequencing

Currently, the main drivers of complexity are the increase in duration, intensity and the number of actors involved. Here again, we call for a paradigm shift.

First, we call for a culture of preparation based on the eight pillars detailed above. This entails the need to provide tools and formalize the capabilities to do and train these capabilities throughout the year – without necessarily making them an event in a big exercise (e.g.: ComEx workshop on the first 10 actions to launch in case of a cyber crash, testing the isolation of backups or the restoration of workstations).

In addition, employing vertical training logic (e.g., enable then simulate), it is important to train the ability to sequence the different capabilities quickly and efficiently. Thus, it is advisable to propose larger exercises, common to the business, forensic and decision-making teams, to orchestrate their different simulations in a single exercise. In training, for example, the detection capacity should be tested with a Purple Team, and then the mobilization capacity of the crisis system with a surprise mobilization using the alternative tools provided. A second example: work on the coordination capacity of the numerous crisis cells over a long period of time and then producing a communication message for all its stakeholders (internal and external).

A long-term commitment

To be relevant, this approach must be supported by strategic, global, multi-year thinking. Since it is more ambitious and involves more stakeholders (SOC, RPCA, Resilience, Infra, CISO, ComEx, Third Parties, …), it can gain legitimacy through a prior empirical evaluation of the means:

- Assess the current state of your readiness by taking a feasibility-centric approach to the eight pillars.

- Establish a maturity target and a roadmap that you will be able to report on empirically over time.

- Finally, share with your management teams a more robust view of your crisis management maturity.

This type of approach, more empirical and personalized, will not only allow you to identify capacity gaps but also to truly train for the actions that will be essential at the worst moment.