The Network and Information System Security – (UE) 2016/1148 directive, commonly referred to as NIS, was a European directive adopted by the European parliament on July, 6th , 2016. It has been transposed by member states into their national legislations until May 9th, 2018. In the United Kingdom, the NIS requirements have been included in The Network and Information Systems Regulation which came into force on May 10th, 2018 and the The Network and Information Systems (Amendment and Transitional Provision etc.) Regulations came into force on December 31st, 2020.

The NIS directive is the first initiative of EU-wide legislation on cybersecurity. Its goal is to ensure a high and common level of security for European information systems and networks. To achieve this objective the directive focuses on four key points:

- Consolidating the member states’ national cybersecurity capabilities

- Creating a political and organizational cooperation framework on cybersecurity across the EU,

- Ensuring the cybersecurity of operators of essential services (OES). OES are private or public entities providing essential services for the maintenance of economic and societal activities. The provision of these services depends on network and information systems.

- Ensuring the cybersecurity of digital service providers (DSP). DSPs are defined as “any service normally provided for remuneration, at a distance by electronic means and at the individual request of a recipient of services”[1]. Three types of services are mentioned in the NIS Directive: Cloud computing services, online marketplace and online search engines.

On the one hand, the security of operators of essential services is a sovereign prerogative of states while onn the other hand, the role of the EU is to ensure the proper functioning of the European market. In order to reconcile these two objectives, the NIS directive clearly states that: “This Directive should be without prejudice to the possibility for each Member State to take the necessary measures to ensure the protection of the essential interests of its security, to safeguard public policy and public security, and to allow for the investigation, detection and prosecution of criminal offences.”[2]. Each country can therefore adapt the legislative text to fit its priorities and strategic objectives as well as to guarantee its security and that of its networks and information systems. The NIS directive, however, sets common requirements in terms of; transposition of the directive into national legislation, of sectors concerned, of risk identification, of supervision, of implementation of technical and organisational measures, of cyber incident notification, and of sanctions in case of non-compliance.

This analysis brings together elements on the transposition of the NIS directive in each of the 27 member states of the European Union, as well as in the United-Kingdom and Switzerland. It highlights the various approaches and underlines the similarities and differences between countries, especially in the context of the upcoming evolution of the legislative text. Indeed, a proposal to revise the NIS directive has been adopted by the European Commission in December 2020 and aims at replacing the original text.

An achieved transposition for certain themes…

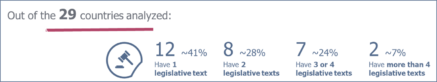

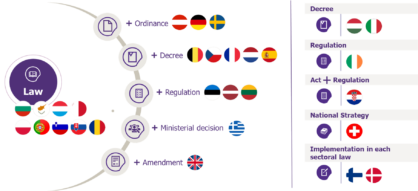

Different types and numbers of legislative texts to transpose the NIS

The transposition of the NIS occurred in all the national legislations of EU member states. However, there is heterogeneity in the type of legislative text adopted. In most countries, the transposition takes the form of a law (twenty-two countries), to which thirteen countries have added at least on other legislative text (ordinance, decree, regulation, amendment or ministerial decision). In two countries, the transposition took place in each sectoral law which increases the number of legislative texts (four texts or more).

A general implementation of cyber incident notification processes

All countries managed to implement cyber incident notification processes. Once again, there are various approaches depending on the country.

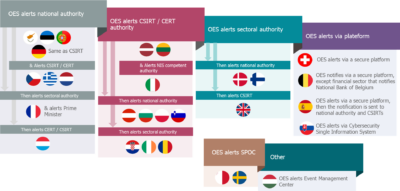

There are six different procedures for transmitting alerts during a cyber incident:

- In the first case (nine countries), the operator of essential services must first notify the competent national authority of the occurrence of a cyber incident,

- A second process (ten countries) exists in which the first point of contact is the CSIRT, the Computer Security Incident Response Team, also called CERT (Computer Emergency Response Team),

- In a lower number of cases (three countries), the OES must notify the competent sectoral authority,

- The notification of cyber incident is carried out via a secure platform in four countries.

- Even less frequently (two countries), the single point of contact (SPOC) has to be alerted.

- Finally, for one country (Hungary), the OES alerts an event management centre.

In addition, all member states must notify the point of contact of a member state, if it is also affected by the cyber incident, and must inform the public when necessary.

To comply with the constraints imposed by the NIS, certain states have even gone further

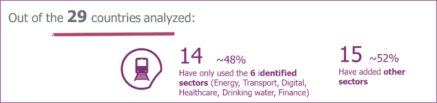

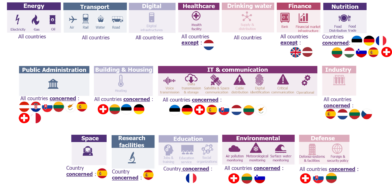

The NIS directive initially applies to the following sectors: transport, energy, health, drinking water, banking, finance, and digital. In the transposition, more than half of the analysed countries added other essential sectors and sub-sectors in addition to the seven previously mentioned. They are listed below, sorted by frequency of occurrence :

- Austria, Croatia, Cyprus, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, Spain and Switzerland also mention public administration,

- Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Spain and Switzerland add information and communication technologies and IT.

- Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Lithuania, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland add

- The Czech Republic, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Spain complete the list with industry.

- Estonia, Germany and Switzerland also mention heating and housing.

- Lithuania and Slovakia subjoin defence, Switzerland national security.

- Lithuania and Slovenia add the protection of the environment.

- France is the only one to add education.

- Spain is the only one to mention space and research centres.

… However, the variation needs to be finalized on other themes.

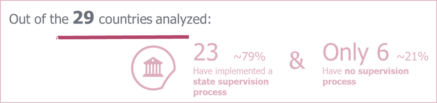

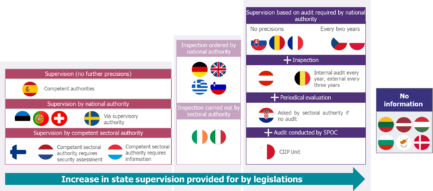

Strong disparities on state supervision

Several categories and different levels of control are exercised by authorities to certify compliance with the NIS. The strong disparities concern in particular the authorities ensuring the control (national or sectoral authority) as well as the expected level of control (supervision, inspection, audit, evaluation…): there is no consensus around the process to adopt. Moreover, six countries do not provide any information on the type of supervision implemented.

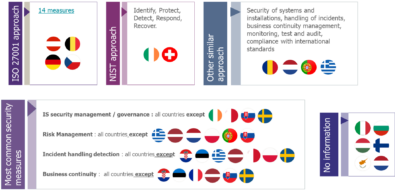

Heterogeneous level and diffusion of security measures

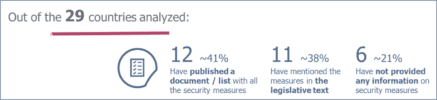

Except for six countries for which no information has been given on the type of security measures implemented, there are two main approaches:

- The security measures are directly mentioned in the body of the legislative text(s) transposing the NIS (eleven countries),

- They are enumerated in; a guide, a list of recommendations, an online publication and established by different entities (government, regulation, decree…) in twelve countries.

For the measures included in the body of the legislative text(s), there are similarities on their organisation:

- The international norm ISO27001 and the cybersecurity framework NIST are used as models to establish the security measures in respectively four and two countries.

- The same six categories (security of systems and installations, handling of incidents, business continuity management…) are used in four countries.

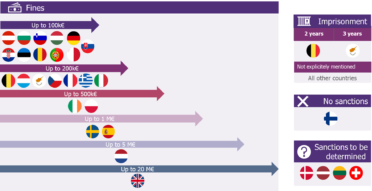

Different amount and format of penalties

The financial penalty for not complying with the directive varies in the different countries and can range from less than a 100k€ to 20M€ maximum (except for Finland which has not implemented any sanctions). Most countries have chosen to apply a fine of less than 200k€ (eighteen countries) whereas four countries have decided that the maximum should be beyond 1M€. It should also be noted that the sanctions are likely to accumulate in the event of multiple non-conformities, which does not make the overall maximum amount of a sanction a certainty.

Imprisonment sentences have been implemented in two countries (Belgium and Cyprus).

Finally, four countries have not yet communicated the penalties in case of non-compliance.

Conclusion

The goal of the NIS directive was to address the unequal levels of security of networks and information systems within the European Union. To achieve it, it has now been transposed in all the member states. This has led to the creation of a common security framework while also leaving the possibility for states to ensure their security and the protection of their essential and strategic interests. Indeed, each country designates its operators of essential services and chooses the sectors it deems the most strategic to protect. In addition, the transposition of the directive as well as the supervision and cyber incident notification processes are carried out by the authority deemed competent. This is non dependantwhether national or sectoral, whether it is the CSIRT or the single point of contact. This flexibility makes it possible for the NIS to adapt to the organisation of all member states. There are visible similarities creating groupings between the countries, as well as major dissimilarities. These leave room for many variations and make the comparison relevant and rich.

A proposal to revise the NIS directive was adopted in December 2020, but its provisional calendar has not yet been communicated. However, its main objectives has been listed and includes reaching a higher level of cybersecurity and more homogeneous processes within the EU, while further increasing the cooperation between member states. The revision of the NIS directive revolves around;

- the abandonment of the distinction between OES and DSPs

- the designation of OES by the Directive and not the states

- the creation of a new European network for major cyber incidents

- imposition of CSIRTs supportive of entities,

- the control by the states of the technical and organisational measures implemented (for risk analysis and crisis management).

These changes will be detailed further in a new article.

Sources :

Directive Network and Information System – Article ANSSI Link: Link to the article on NIS Directive

Directive (EU) 2016/1148 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2016 concerning measures for a high common level of security of network and information systems across the Union Link : Link to the NIS Directive

On Digital Service Providers (DSPs) – ANSSI Article – May 23rd 2018 Link : Link to the article on DSPs

On Operators of Essential Services (OES) – ANSSI Article Link : Link to the article on OES

Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, repealing Directive (EU) 2016/1148 Link: Link to the proposal of the revised NIS Directive

[1] Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 September 2015.

[2] Directive (UE) 2016/1148 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2016.