Is it necessary to engage in DevSecOps because projects work in Agile? A few questions need to be asked to get a clearer picture.

In previous articles, we talked a lot about how security should be organised to accompany agile projects: the change in the security paradigm to ensure Security by Design, how to organise the ISS teams in the face of these changes, the possible methodologies for continuing to analyse risks or get security approvals (and a general reminder of what security looks like in agile).

These articles were mainly about the organisational and methodological paradigm shifts that ISS teams were undergoing, to be able to best support projects, which deliver code much faster.

The links between Agility and DevOps

By shifting the focus towards the development teams, it is now a question of dealing in greater depth with software solutions and processes enabling security to be integrated directly into the development pipelines and into the daily lives of developers, where Agile and DevOps methodologies, although they aim to provide the best value to customers, will be expressed differently.

As the DevOps movement was born later than Agile methods, development teams were organised earlier than operations in an iterative and rapid mode for application and service delivery. DevOps principles bridge this gap by bringing Operations and Development teams closer together, and by offering solutions to accelerate delivery through the strong automation of the software development lifecycle, via CI/CD pipelines. In the end, the two approaches feed off and complement each other, to deliver faster and with better quality, thanks to the automation of a large number of tasks, thus avoiding human errors.

What about security?

Back to our topic of interest, it is now a question of automating security as much as possible. Just like the Agile and DevOps methods, Security in Agile and DevSecOps are also closely related. The idea is to bring security closer and closer to the development teams, but also make it as fast as possible. A key profile of the security principles in Agile is perfectly suited to DevSecOps: the Security Champion. As described in the article “How to structure SSI teams to ensure security in Agile at scale“, this is the security ambassador within the development teams. They are an integral part of the product team and are present in every sprint. Their role is to ensure that security is considered in each sprint in the development of User Stories (by integrating Evil or Security User Stories already written, or by helping to write them). The Security Champion can come from the world of development and become more skilled in security issues, with the help of the Security Guild.

To take it a step further, the Security Champion can also help their team understand automated security solutions, with the help of a specialist from the ISS team, who will help them to develop their skills in application security.

Having said that, is it because Agile Security and DevSecOps are linked that one should automatically embark on a transformation programme towards DevSecOps?

Some preparatory questions for embarking on DevSecOps.

In line with any major transformation project, it is worth asking why you are doing it, making sure you have a plan and the right sponsorship. DevSecOps is no exception to the rule, even if the questions to ask are specific.

Defining the scope and objectives

Firstly, before you start, you need to identify your motivating factors. Is it to deliver faster? Better? More securely? Will the problems encountered by the Dev, Sec and Ops teams be resolved by bringing the skills together? This is to prioritise efforts and ensure that the project can be ‘sold’ to sponsors. Next, the scope must be identified, trying to delimit it between transitional scope (short and medium term) and target scope (long term). Work can start on an application portfolio, a factory for testing, followed by creation of a roadmap for deploying the model to the full scope.

The current maturity of the organisation in terms of tooling and automation in the product development cycle should be assessed. A good knowledge of the tools used in the pipelines is a prerequisite. If there are still too many grey areas, an inventory of existing tools and an inventory of the practices and processes in place should be put together first.

Presence of the essential building blocks of the CI/CD pipeline

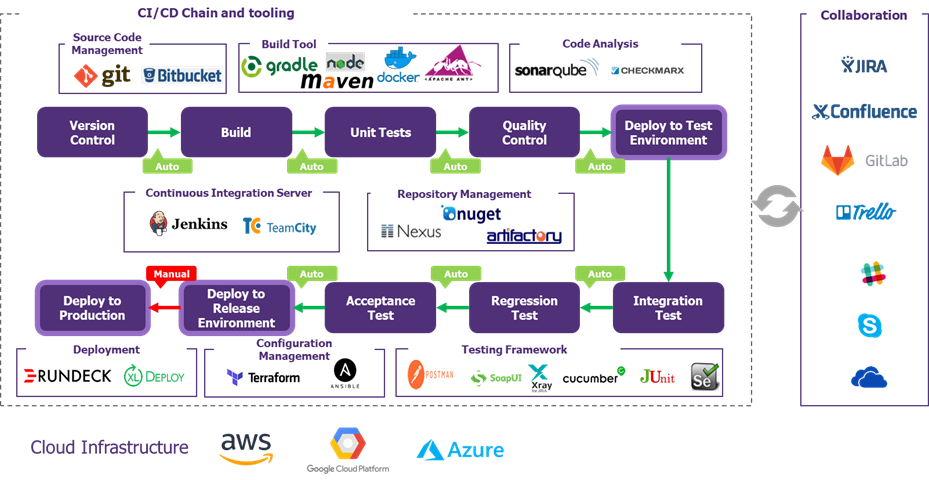

Before security can be integrated into development pipelines in an automated manner, it is first necessary to ensure that we have a good vision of what a state-of-the-art pipeline might look like. It is possible to embark on a DevSecOps programme without operational pipelines already installed but having a clear idea of the target is key. Here are some examples of solutions:

Figure 1 – the essential building blocks of a DevOps pipeline

The company must also be able to quantify the developments carried out internally or externally, with development agencies. Indeed, a complete pipeline will be useful for companies developing mainly in-house: it is an indispensable tool for developing quickly, with the right security tools integrated into the pipeline. In the case of external developments, the principle is different, and security is less “easy” to control: agencies will not necessarily give access to their pipelines or their source code. They may only deliver executables or images, via remote repositories for example. Integrating security is therefore done by more traditional means: via Security Assurance Plans (SAPs) for example, or by contractually obliging agencies to train their developers in application security, via training software solutions (for example CodeWarrior, which delivers ‘belts’ according to the level of training achieved).

Secondly, one of the most important ideas is that the pipeline is built in stages. In line with the “test and learn” approach dear to Agile methods, a “pilot” version of the pipeline can be deployed for a volunteer product team to test it over a few weeks/months. The deployment is then carried out progressively, according to a pre-established roadmap. In most cases, companies first set up a DevOps pipeline, with a few codes analysis tools (most often quality-oriented), then, once the pipeline is considered functional, the security tools are added.

However, it could be worthwhile to consider security tools as an integral part of the CICD pipeline. They could then be integrated into it progressively, according to a prioritised roadmap, as proposed below.

Here are some examples of tools that make up the security stack:

Figure 2 – Examples of security solutions to be integrated into the CICD pipeline (DevSecOps)

According to our feedback from the field, some tools are “easier” to implement and are therefore implemented as a priority.

Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools

As mentioned earlier, these tools are nearly always already present in the initial pipeline, in their code quality testing format. Here it is a matter of configuring them to go one step further and perform security analysis of static code. This type of tool can be integrated at several points in the pipeline, in a “shift-left” logic, i.e., integrating security as early as possible in the pipeline. It can be positioned directly on the developers’ IDEs (integrated development environment), to provide them with “real-time” feedback on errors that could introduce vulnerabilities. It can also be used at the time of code compilation.

A disadvantage of this type of tool is the high number of false positives. The configuration is scalable and improves over time. However, the governance and processes around the tool need to be thought out in advance: a vulnerability triage team can be a solution, as well as training security champions to spot false positives, with the help of an application security expert (an Application Security Engineer for example).

SCA (Software Composition Analysis) tools

These tools should logically be installed as a priority, as developers make great use of open-source libraries to develop their products. The SCA will check the components of the library, such as licences, dependencies, vulnerabilities, and potential exploits. Many attacks originate from the uncontrolled use of open-source libraries that may contain critical vulnerabilities (such as the Log4Shell exploit).

This tool can be used like SAST, on IDEs or before compiling the code.

DAST tools

DAST tools scan running application builds for security vulnerabilities. They allow the simulation of a malicious attacker’s behaviour through automated pen tests and detect common security vulnerabilities such as OWASP 10. These tools may be less easy to use in authenticated mode (authentication is difficult in automatic mode, it must be done manually before running a test). The tests also take longer than a static scan, and dedicated time must be set aside so as not to disrupt the work of developers or production.

They can be used at the time of testing, but also in production.

It is necessary to think very early on about the governance and processes to be put in place around these tools, in particular by ensuring that developers cannot ignore detected vulnerabilities (by passing them as “false positives”, for example) and to ensure that vulnerabilities are centralised in a single tool (vulnerability management tool, for example), for greater efficiency.

Checking the presence of enabling technical prerequisites

The interest in working in DevSecOps may be limited on non-configurable and non-instantiable software package type applications.

On the infrastructure side, Infrastructure as Code (management and provisioning of infrastructure via code rather than manual processes) allows the use of containers or provisioned VMs that are key to use CICD pipelines more efficiently.

Not forgetting the whole governance and change management layer around the project

Make sure you build, or already have, an operating model that meets your needs (security champions, enabler teams, tooling, processes). Working in “agile at scale” mode is not mandatory for the first iterations (depending on the scope chosen).

Using a “test and learn” method to experiment is a good way to involve the teams very early on, and to get complete and relevant feedback from the field, before starting to deploy at scale. Cybersecurity experiments have been carried out with clients to find out what types of practices or tools to implement.

Some examples:

– Purple teaming to allow developers to see the results of another team’s testing tools and attempt to exploit them (allowing developers to see the reality of an attack and the potential ease of carrying it out),

– Implementing solutions such as Cloudbees, to automate the CICD pipeline processes,

– Training Security Champions to interpret the results of security tools.

These experiments also act as change management, as most stakeholders can be involved early in the transformation programme.

In conclusion

CICD pipelines are a real opportunity for security to become automated. By integrating the right tools into the pipeline, developers are supported in their practice, kept on real security guardrails, facilitating the development of a secure product.

In addition to securing the products, it is also a question of securing the pipeline itself, in the same way as any component with broad access to the information system: it is a question of controlling access to the various tools that make up the pipeline, ensuring that secrets are properly managed, that the underlying servers are hardened, etc.

In a future article, we will detail our views on the pillars of DevSecOps, or how to achieve a sustainable and effective transformation (based on shift-left, guardrails and empowerment of the teams on security!).

Any comments or corrections? Do not hesitate to contact us!