A 38% increase of cyber-attacks was estimated in 2022[1]. As this figure illustrates, the cyber threat continues to grow, and has become a major concern for businesses worldwide. To counter this growing threat and maintain digital confidence, governments have long been regulating cyberspace, and continue to do so to adapt to changing conditions. As a result, we have seen the gradual emergence of multiple regulations requiring the implementation of cybersecurity and data protection measures, accompanied by different levels of possible sanctions in the event of non-compliance. Companies are now faced with a complex regulatory landscape, requiring the implementation of compliance strategies with adapted organisational models.

A denser and more complex cybersecurity regulatory landscape

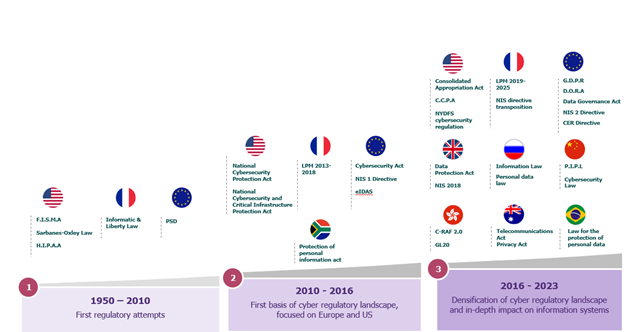

The first attempts to regulate personal data protection and cybersecurity remained partial until the early 2000s, being driven mainly by the United States and the European Union. Initially, they focused on the protection of personal data, in France with the Loi Informatique et Libertés (1978) and in the United States with sector-specific regulations: the Privacy Act (1974) for the public sector, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act for the healthcare sector (1996) and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (1999) for the financial sector.

The first cybersecurity regulations were introduced in the financial sector in the early 2000s, with the aim of improving the security of the services provided. Notable regulations include the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002), in the USA, reinforcing corporate transparency in terms of internal control, and the Payment Services Directive (2007) in the European Union, regulating the security of online payments and transactions.

Since the early 2010s, more structuring regulations have emerged to form an initial cyber regulatory base in the same regions. These regulations are mainly focused on critical infrastructure protection, with France’s Loi de Programmation Militaire de 2013-2018 (2013), the USA’s National Cyber Security and Critical Infrastructure Protection Act (2014), but also the Network and Information Security 1 Directive (2016) enacted by the European Union.

It wasn’t until the late 2010s that the desire to regulate the cyber space became more global. As many countries followed in the footsteps of the United States and the European Union, stricter cyber regulations began to emerge, with far-reaching impacts on information systems. This can be seen in the arrival of major personal data protection regulations around the world: the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, 2018) in Europe, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA, 2020) in California, the Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL, 2020) in Brazil, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL, 2021) in China, or the Personal Data Law (2022) in Russia.

Other regulations aimed at protecting information systems are multiplying, with the Cybersecurity Law in China (2017), the NYCRR 500 Cybersecurity Regulations for the State of New York (2017), or the new iteration of the NIS Directive (2023) and DORA in Europe.

Evolution of cybersecurity regulatory landscape[2]

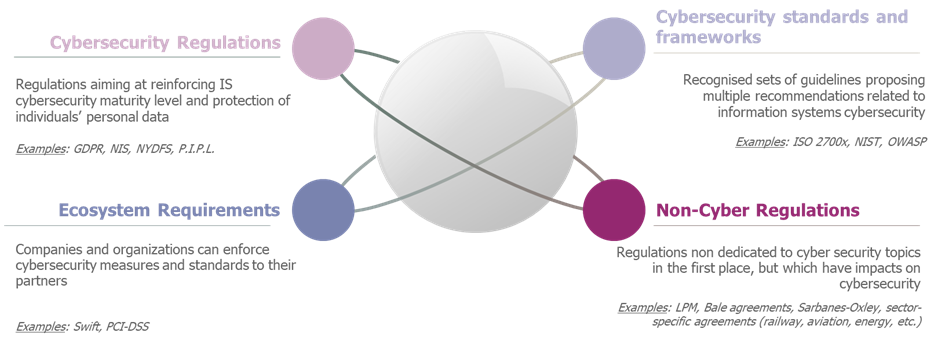

Added to this complex cybersecurity regulatory landscape is a vast ecosystem of cybersecurity requirements and standards, with different levels of constraint: regulatory requirements stemming from cyber or other regulations, mandatory requirements, recommendations or even requirements with contractual value. In this context, it is essential to identify all applicable requirements and the level of constraint they impose.

Types of cybersecurity requirements and standards, beyond cyber regulations

A cybersecurity regulatory compliance strategy adapted to the new paradigm

With the global cybersecurity regulatory landscape becoming increasingly complex, compliance cannot be thought of solely as total compliance with all applicable regulatory requirements. Faced with detailed, costly and sometimes contradictory requirements, it is becoming necessary to implement risk-based cyber compliance strategies. The definition of these strategies will be based on a study of the existing level of regulatory compliance, an assessment of the effort and complexity of the measures required to comply with each regulation, and a consideration of the risks associated with potential non-compliance, both in terms of sanctions and IS protection. This analysis, far from seeking to escape the law, aims to identify the benefit/risk of activities, and may lead to redirecting activities, limiting their scope, or acting in concert with the ecosystem to evolve requirements.

To implement such a strategy, it is first essential to identify all applicable regulations, and to set up a regulatory watch to keep alongside regulatory developments and related news. A two-tiered organisation must then be set up to manage cyber regulatory compliance.

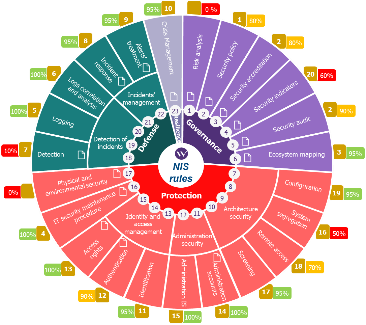

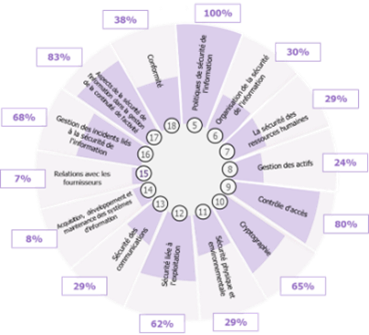

A first level of overall management aimed at providing a high-level overview: a global analysis of the level of cyber compliance must be carried out. This can be based on a recognised cybersecurity standard such as NIST or ISO 27001 for security requirements. For requirements relating to the protection of personal data, GDPR is a good foundation, since most international regulations on this topic are derived from it. The NIST privacy and ISO privacy standards are also solid references in this field. These benchmarks can be mapped onto the main applicable regulations, and advantage can be taken of existing synergies between regulations, as illustrated by the two examples below.

To complete this analysis, an audit plan should be drawn up to assess compliance with key local regulations in greater detail.

| Analysis of synergies between the NIS Directive and the LPM | Analysis of synergies between the NIS directive and ISO2702 |

A second level of “local” management, on a geographical or business line scale, aimed at ensuring local regulatory compliance in each of the regions where the Group is present. This requires first of all the implementation of a local watch to identify and know precisely the regulations and associated news. This is followed by a detailed analysis of the level of compliance with local regulations, the identification of specifics needed to ensure the right level of compliance, and the feedback of these elements to the Group to ensure the overall management of compliance actions.

Protection regulations call into question the need to separate information systems

Complying with a multitude of cybersecurity regulations is becoming a real challenge for companies with an international presence and centralised information systems. This is due to the stacking up of these regulations, sometimes with incompatible or contradictory provisions, but also to the emergence of requirements with far-reaching impacts on information systems.

This is the case, for example, with China’s PIPL regulations, and in particular Article 40, which stipulates that the transfer of data outside China will only be authorized if processing complies with the security assessment established by the Chinese authorities. This regulation will apply above a certain volume of personal data (not yet specified by the Chinese authorities).

Incompatibilities between regulations have also arisen between the United States and the European Union. This is illustrated by the invalidation of the U.S. Privacy Shield[3] by the European Court of Justice, its Schrems rulings calling into question the ability of U.S. Cloud hosts to process the personal data of their European customers in line with European requirements.

Against this backdrop of heightened cybersecurity and personal data protection requirements, emphasised by the protection intentions of certain countries, it may become necessary to study the need to separate globalised and centralised information systems by considering separation into several geographical zones, which could be:

- A zone comprising the USA and the UK

- A second zone centered on China

- A third zone made up of the European Union and GDPR-relevant[4]

Depending on their regulatory reality and potential developments, other countries or regions could be attached to one or other of these three zones.

In the future, the information systems of these different zones could rely more heavily on the sovereign clouds that are currently being developed.

Constraints that can even lead to the closure of a region’s operations

We’re even seeing a number of companies halting or postponing the launch of activities in certain countries where the regulatory constraints and associated risks of sanctions are too great in relation to the business challenges and strategy of the company. This is particularly the case in certain US states, and in Europe, where some major players are putting the brakes on their development because of the RGPD (e.g. Google’s open AI/ Bard, or Meta’s launch of Thread).

What’s next for 2023 and beyond?

The complex regulatory landscape will continue to expand in the months and years ahead. Both in new areas (AI, product security) and in existing areas, such as critical infrastructure.

On the “critical infrastructure” front, after the first phases of regulations focused on personal data protection, the authorities have been looking at critical infrastructure protection, which continues with the NIS2 directive in particular. Adopted on November 10, 2022 and soon to be implemented into French law, it aims to reduce disparities between member states, strengthen cybersecurity in a context of increasing digitalisation, and establish security measures to improve the level of security of critical infrastructures within EU member states.

A new phase is now taking shape, during which regulations will focus on the safety of digital products, with in particular:

- The AI Act, a European regulation aimed at defining a common frame of reference for the development and use of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Against a backdrop of lightning acceleration in the uses of AI, new regulations are also set to emerge around the world, and particularly in China, where measures have already been taken and led to the closure of 55 applications and 4,200 sites between January and March 2023[5].

- The Cyber Resilience Act (C.R.A), another European regulation, which aims to strengthen the security of digital products by imposing measures to be respected by manufacturers right from the product design stage. Not to mention the recent announcement by the White House of the “Cyber trust mark” initiative, which targets the same objective but with a different approach[6].

The regulatory stakes are not about to diminish, and cyber teams need to be prepared. At the very least, it will be necessary to strengthen links with the business lines concerned, as well as with legal teams. The most mature companies in this field have set up legal departments within their cyber teams, to exchange information with the various legal departments. This may not necessarily be necessary, depending on the organization of each structure, but it can also be a guarantee of strong mobilization.

In all cases, the challenge for companies will be to transform these often mandatory regulatory requirements into a competitive advantage for their business, not by punitive, minimal compliance, but rather by taking ownership of the subject and transforming these practices in a way that can be leveraged externally.

[1] https://blog.checkpoint.com/2023/01/05/38-increase-in-2022-global-cyberattacks/

[2] Non-exhaustive list of cybersecurity regulations

[3] https://www.cnil.fr/fr/invalidation-du-privacy-shield-les-suites-de-larret-de-la-cjue

[4] Countries complying with the level of protection required by the EU https://www.cnil.fr/fr/la-protection-des-donnees-dans-le-monde

[5] https://www.01net.com/actualites/comment-les-lois-chinoises-tres-strictes-risquent-de-nuire-a-lia-made-in-china.html

[6] https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2023/07/the-cyber-trust-mark-is-a-voluntary-iot-label-coming-in-2024-what-does-it-mean/